James Earl Cox III has more than 40 games on Game Jolt and quite a few more floating around out there. He’s a student of game design, and has become an influential indie developer himself over the last couple of years. If you’ve played a few of James’ games, you know that he’s unafraid to experiment and challenge the player. His work presents a wide range of player experiences and a lot of it questions the very idea of what a game can be.

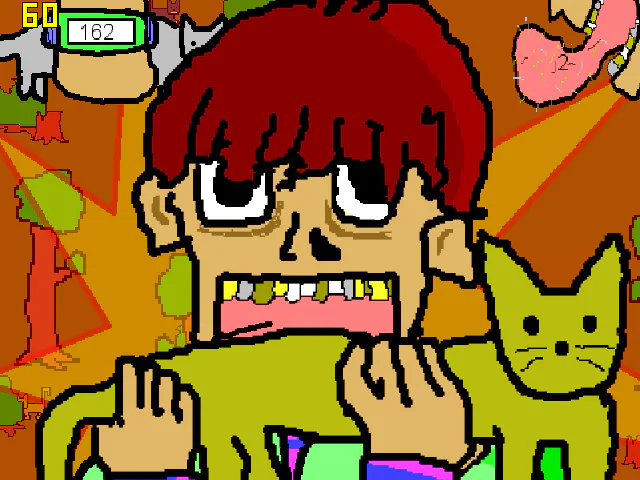

It’s been tremendously interesting to watch James’ style and skills develop since his early releases like Cat Licker. He’s got a unique voice and a plethora of ideas swimming around in his head, and every one that bubbles up to the surface in the form of a new game is exhilarating.

I had so much I wanted to ask James, and he gave me some lengthy answers, so we are splitting this interview into 2 parts. The second part will be posted on Fireside in a week. And now, the first part of my conversation with James Earl Cox III:

{% pullquote Crab Dungeon Full of Dungeonous Crabs %}

Paul Hack: Hi James, thanks for taking time to talk to me. So, you’ve made a lot of games. In fact, you’re about halfway through a quest to make 100 games in five years, as revealed in your recent article. What was your first game and how far would you say you’ve come since then?

James Earl Cox III: Thank you for offering!

As of now, I’m a little over 60 games into the challenge and just beyond the 2.5 year mark; feeling pretty confident that I’ll be able to reach this goal! Besides drawing mazes and levels for videogames I dreamed of creating one day, I think the first playable game I made was a table top strategy game in elementary school. It used little stick figures doodled on scraps of paper for units. When I played it with friends, we’d use the sides of note cards for measuring distances: soldiers could move one notecard, horsemen could move two. However, the first game-like activity that I’m really proud of was amassing an army of buckeye nuts.

One of my school’s fourth grade teachers was from Ohio, and she would give out little buckeye nuts (as the Buckeye tree is the state tree of Ohio) to kids that did well in class. A friend of mine in the class, Kat, put clay on her buckeye so that it had a little face and hair; she named it ShayShay. I loved that idea, so I made a buckeye emperor named Scar. He had a purple cape and a robotic prosthetic eye that covered a small crack in the nut (which is why his name was Scar) and a Viking helmet with horns on it, all molded out of clay. Every buckeye I was given beyond Scar became a soldier in his militia.

{% pullquote Cat Licker %}

Some classmates were intrigued by this miniature platoon of buckeyes I had forming at my desk and asked if their buckeyes could be a part of this army too. Thus Scar began conquering the classroom, desk by desk. Now the problem was that my family has roots in Ohio, and since I would collect buckeye nuts by the bucketful whenever we visited relatives there, I ended up with a lot of buckeyes.

Eventually, my brother Joe and I had a buckeye army over 200 nuts strong. We built a mega tank for them out of cardboard and note cards that stood about four feet tall with sleeping quarters and an armory inside of it for all of the nuts. I also drew comics of Scar’s adventures. Eventually the buckeyes began to decay, so we moved onto other creative hobbies.

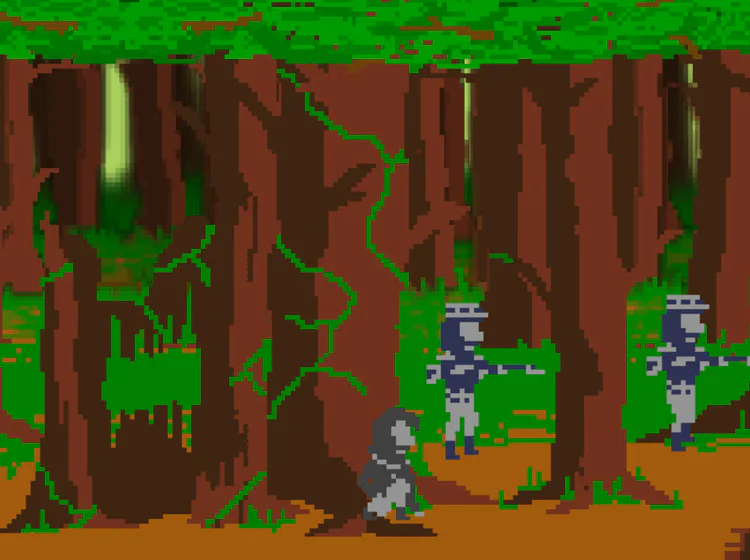

{% pullquote Kill the Kraken %}

Although I haven’t made any strategy videogames, I think elementary school James would be impressed with how many games future James has made. In terms of strategy field games, he would probably love to play Kill the Kraken too, although he wouldn’t be allowed, being too young and all. I should try to find those buckeye comics at some point.

Paul: Tell me a little about the game development program at USC that you’re a part of.

James: For sure! I’m currently a graduate student in the University of Southern California’s Interactive Media and Game Design MFA program. The program itself is embedded within the School of Cinematic Arts. Most days you can see film students running around outside lugging heavy film equipment and setting up lights for shoots.

The Interactive program is three years long. The first two focus on expanding and honing our design and development skills. Then the last year is thesis year, where we spend both semesters crafting a larger project with guidance from faculty and outside mentors. Lots of amazing people came from this program: Day9, Asher Vollmer, Jenova Chen, Kellee Santiago, and Palmer Luckey to name five.

The cohorts are relatively small with around 15 students accepted a year, so it’s a pretty close knit and supportive group; colleagues are always happy to lend a hand. The faculty is amazing, too. This semester I’m taking a class under Richard Lemarchand, and I had a class last semester with Tracy Fullerton, both amazing experiences. What I love most about the program is how driven and welcoming everyone is.

I may be a bit biased and sappy about USC, but to be fair, this is a program I spent my undergraduate years working towards. It’d be strange if I didn’t like it this much!

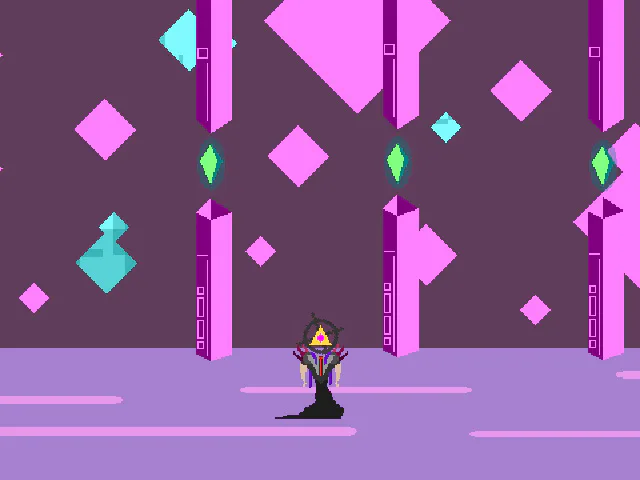

{% pullquote Garugol %}

Paul: Why did you choose to go into making games rather than film or another artistic field?

James: I’ve always loved telling stories and creating experiences: comics, theatre, drawing, even a bit of singing and painting (the singing might be a bit painful to hear, though). The three mediums I fell in love with at University were writing, filmmaking, and game crafting.

I started off my undergraduate journey at Miami of Ohio as an English Creative Writing major. I remember hosting writer workshops with my classmates and friends, giving each other feedback and encouragement. I managed to have at least one story published per semester in the campus literary magazine Inklings and even had a few pieces published in non-Uni magazines: “My White Shirt”, “Tomatoes”, and “Hope”.

Yet writing is a hard medium to break into. Not the writing itself necessarily, but getting your work out there. We’d spend days researching and submitting to dozens of magazines. Getting a single story into any sort of publication was a triumph. So I added on Mass Communications as a major to try my hand at film.

The Mass Communications major was great and taught a good deal about film theory and criticism, but the issue with film is that you need props, locations, equipment, money, software, and people (actors and crew) to make most of it come together. Two live-action films I co-wrote with Robert Million Horn are springing to life thanks to his drive and enthusiasm: Unitaur and Llamagedon. We have a few pick-up shots left in both films that we’ll shoot this summer. And then just a lifetime of knowing that we made such bad films. We’re aiming for Thankskilling bad; I wouldn’t dare compare what we’re making to Troll 2 or The Room; those are god-tier. But I didn’t meet and start collaborating with Rob until later on, after I added on Interactive Media as a third major and dove into games.

{% pullquote An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge %}

The secret to games is that you can make games about anything; while this holds true of any media, it seems like we still haven’t embraced it as fully when it comes to interactive media. And if you scope your game right, you can make it with very little code knowledge (tip: physical games take no coding knowledge!) Moreso, I fell in love with making games because, unlike short fiction or film, the audience lives it. Rather than watch a success story, the audience can experience it first hand. And that’s pretty neat. Another reason for why I went into game more permanently is because of Lindsay Grace, a mentor to me during my time at Miami. He inspired me to make critical games as well as design using verb-based mechanics; two elements all of my games embrace to varying degrees.

While I still go back to other means of story telling on occasion (not including singing), games are sticking pretty well. My brother/collaborator Joe and I are growing a fascination with installation-based art right now, so we’ll see where that goes!

Paul: In a nutshell, tell me: Who is Joe Cox?

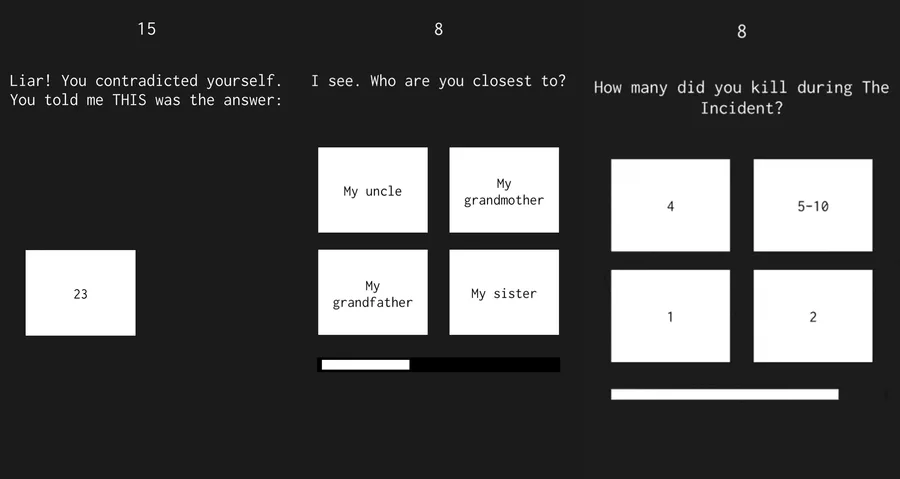

[James answered with the images below -Paul]

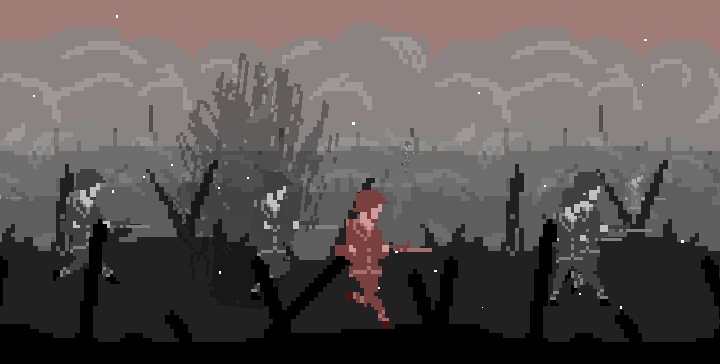

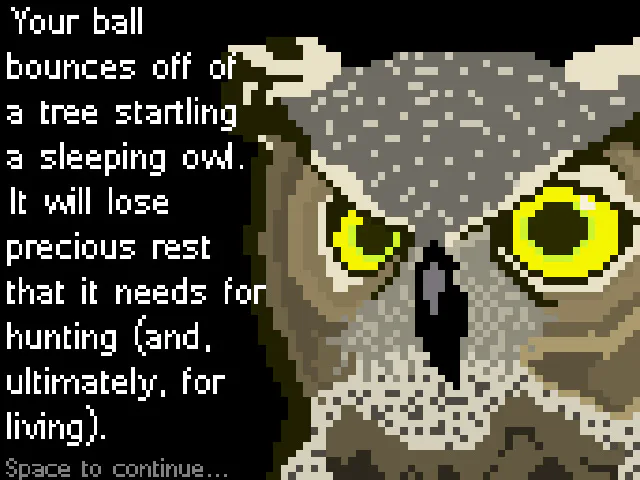

Paul: The game that really put you on the map for me was An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge, based on the classic Ambrose Bierce story, which was also made into a famous short film that was used as a Twilight Zone episode. You’ve since done another wonderful literary adaptation, Ray Bradbury’s The World the Children Made. What do you like about adapting short fiction and do you have plans for any more?

James: Something I really enjoy about intermedia adaptation games is how it’s a relatively unexplored area in plain sight: games that are gateways to literature; not quite educational games, yet more meaningful than mechanics wearing a narrative mask. They convey the short story, as accurately as possible, through an interactive medium. Using mechanics to further the plot in a meaningful way, rather than try to force the narrative onto a conflicting set of rules.

{% pullquote The World the Children Made %}

The Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets game is a great example of a poor adaptation. I remember a part where you’re in herbology class and then the teacher orders you to climb through a small hole in the wall. You end up in a greenhouse maze full of deadly plants and all I could think was “what a sadistic teacher” and “this was never in the books.” It doesn’t add to the plot really, just makes the game joltingly flow like an awkward chimera of novel and videogame. If anyone was told to write a book based off the game, it wouldn’t be very good, nor resemble Harry Potter.

With that said, the first thing to do when making an intermedia adaptation is think “could someone who read the written work have a deep conversation about the story with someone who played the game?” The experience should keep the essence of the story intact: theme, mood, tone, and plot.

My personal goal with these games is to convey them with as little text as possible: if we’re adapting these games from literature, it feels a bit like cheating if we rely on written language.

I plan on making more for sure! There’s a few incomplete adaptations hiding on various thumb drives as of now: another Ray Bradbury and then a Lewis Carroll come to mind. If I have the time, I’d love to adapt the entirety of The Illustrated Man and release it as a .zip. I also had a huge idea for The Decameron, but that’ll have to wait a few years if it ever happens.

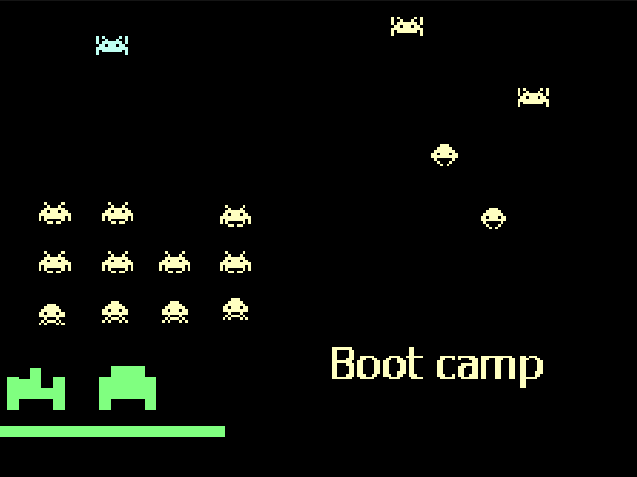

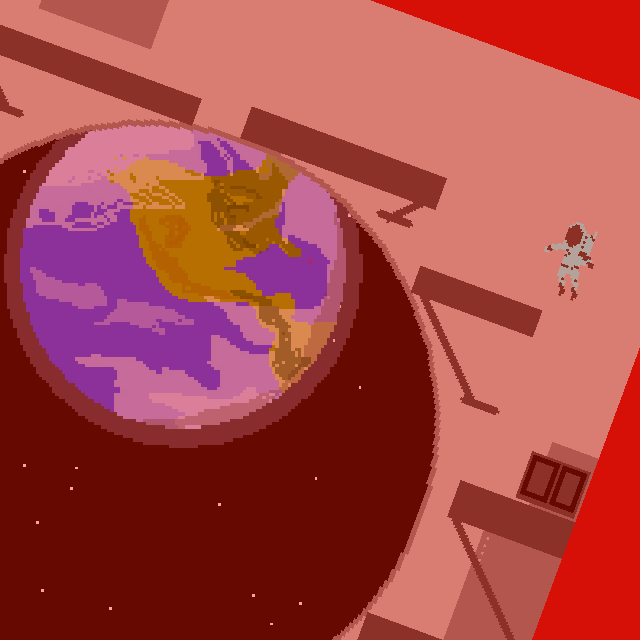

{% pullquote Landers %}

Paul: You have an interest in so-called “critical games”, which sounds very scholarly. You’ve called both Landers and The Mole People Must Pay “critical games”. Could you define that term and tell me how those two games are examples of it?

James: Critical games are interactive media that question our accepted conventions of games. Games can be about anything really, but we have these notions that certain topics would make for better games than others. Where, in reality, games can be about anything, really. Critical games help expand the horizon of game topics and accepted play by making us ask why we keep certain conventions and what would happen if we altered them. For instance, if you made a Mario game where you jump to hit a block with your head, and then it cracks your skull (because it would), it could be a critical game, albeit not a very powerful or deep one. I wrote out a list a little while back with 12 freeware critical game examples for a bit more context. All of my games contain critical elements, but the ones I consider to be fully critical games are the ones created for the purpose of critical play.

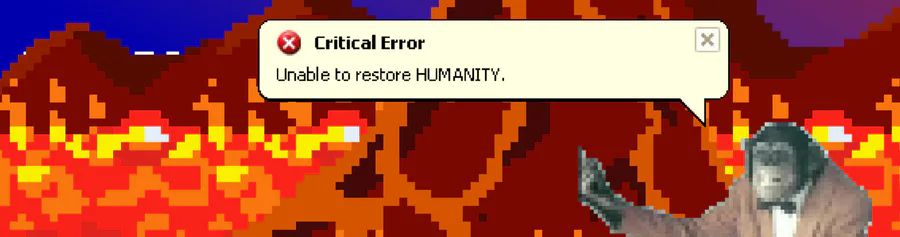

Landers is a critical game about perspective; rather than play the tank and shoot down the invading aliens, it puts the player in the role of an invader and provides a backstory for the arcade game. Outside of goombas and goblins, the uniformity and synchronized movement of the space invaders felt like the perfect example of a faceless other; how opposing soldiers in war games are always baddies, stripping away the humanity from these simulated interactions. Landers was my first fully self-created game; it could use a facelift for sure, yet it was my first attempt to add significance to an otherwise binary system of good and bad.

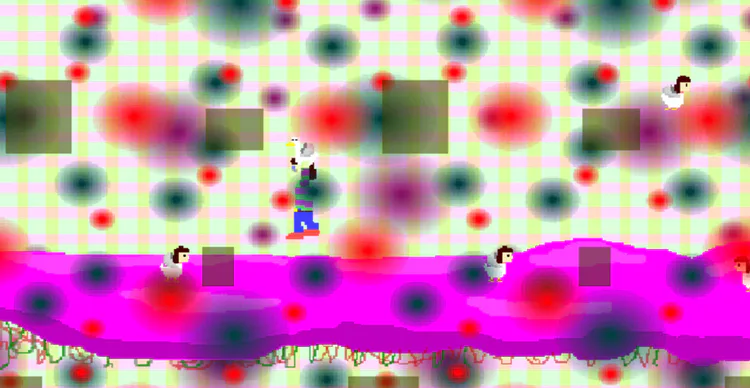

{% pullquote The Mole People Must Pay %}

The Mole People Must Pay runs in a similar vein, now that I think about it. Rather than question the humanity of “the other”, it’s more critical about the way we fill in narrative gaps and how we buy into mechanics blindly. It’s a one button game, so the player can only use space. And you use space to chase down mole people and punch them, yet they never fight back. The title is The Mole People Must Pay and you beat up mole people, so they must have done something bad, right?

Paul: A few of your games explore the idea of authority in games. Both Don’t Kill the Cow and [The Duck Game]( http://gamejolt.com/games/other/the-duck-game/12341/) challenge player freedom in different ways. Are things like goals and winning and losing vital components to a game?

James: My definition for a game is as follows

“A game is the illusion of:

a set of rules

an end state

a feedback system

and voluntary participation”

{% pullquote Don’t Kill the Cow %}

As such, my definition of a game borrows heavily from Jane McGonigal’s with one important difference: games do not need any of these individual components; the player just needs to think they exist. As long as the player believes that these elements (rules, outcome, feedback, and voluntary pariticipation) factor into the game, then it is a game.

With that said, definitions are meant to be bent and broken; it’s just that a Digital Wizard must know the definition before breaking it.

Tying into the idea of critical games, “winning” and “losing” are great for games involving more than one player, as it can create comradery and competition, but we really don’t need “lives” in single player videogames anymore. The “game over” lose state is a vestigial artifact left over from the arcade era.

The arcade machine model is based off of pitting the player against the game. It sets up a symbiotic (or parasitic, depending on your view) relationship with the audience where the player is literally competing against the machine. You want to beat the game in as few quarters as possible, and the machine is built to take as much of your money as it can. So you die, and you feed it more cash to continue.

{% pullquote The Duck Game %}

We don’t need that any more. As soon as players could own videogames in their own homes, this artificial difficulty lost its meaning. Losing, in most games, now has become just an accepted norm; it’s a sort of meaningless delay that prevents the player from completing the game, jolting the player back to reality for no real purpose, more often frustrating than not.

Yet, games like Super Meat Boy are great because they recontextualize the death mechanic into something meaningful: masocore games. These are games that are so brutally unforgiving that winning often equates to key memorization. Roguelikes are another good example of meaningful death. The procedural generation makes each play different enough to feel a sense of loss when you die, a unique world gone due to your errors.

Don’t Kill the Cow and The Duck Game muddy the waters of goals and winning and losing. Of course these two games have no false fail state (I try my best to avoid the inclusion of pointless death mechanics), but they question authority, specifically the game’s authority. We take games’ judgment as law. If the game tells you “you win” or “you lose” then we usually believe it. The best interaction I’ve seen with Don’t Kill the Cow was at Meaningful Play Conference, when a player “lost” and promptly told the screen, “No game, you’re wrong. I won.”

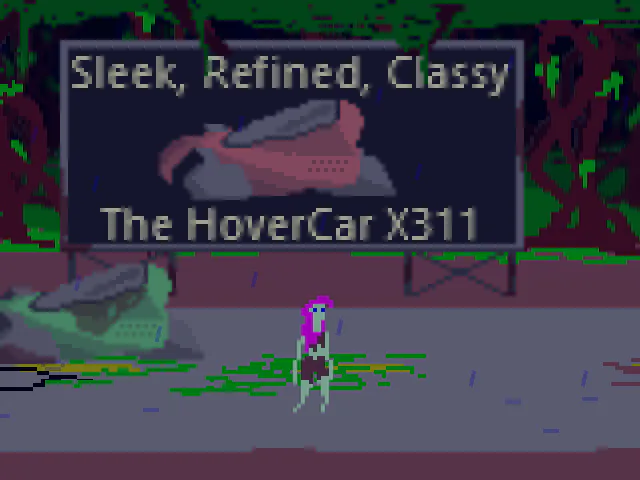

{% pullquote Garugol %}

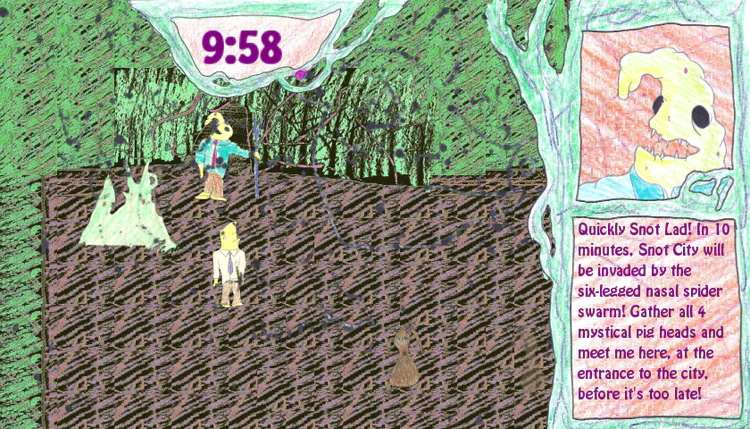

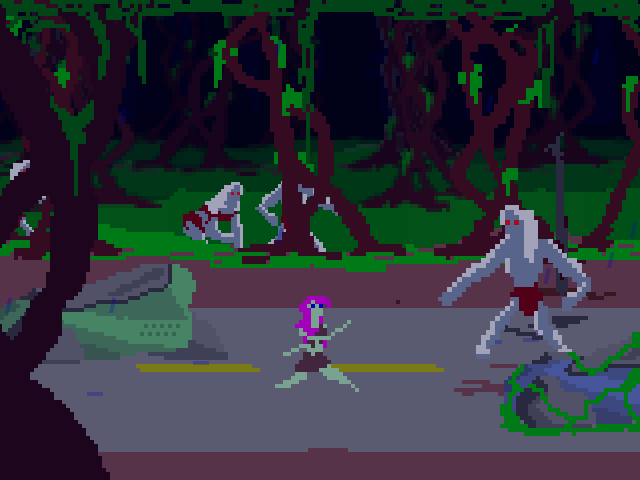

Paul: In the games we’ve discussed—in fact, in a lot of your games—you like to play around with subverting player expectations. Two good examples of this are Snot City and Garugol, Lord of Shadows, executively appointed Arch Duke of the Pyramid Realm. How do expectations shape player experience in these?

James: Garugol was actually Joe’s idea. He also did all of the character artwork for it (he’s really good at making detailed pixel art, especially when it comes to fish horses, fish eagles, and everything in Envirogolf

{% pullquote EnviroGolf %}

Both of these games feel very time-piece-ish. They kind of abuse the conventions of modern gaming that I mentioned earlier. Garugol is a game about getting a promotion. So you get a promotion. And then that’s it. Joe and I were waiting somewhere for something to happen, as we often are, and he pulled out a pencil and started doodling.

His idea was to make a game with these fantastic creatures in this strange and enticing setting, but they all work in a white walled office, and their lives are as boring as ever.

Snot City is a not-broken broken game that can’t be won (but don’t tell anyone that because it’s funnier to watch them struggle with it).

It is true that they both rely on the player buying into common gaming conventions for a first experience, but I’d like to think they can live on as pranks to pull on others. Subverting player expectations is always fun. It’s kind of like opening a can of soup and realizing that it was actually a can of spiny cockroaches. Except that wasn’t funny when it happened to me.

It was not ok for the soup company to subvert my belief that a soup can would only contain soup.

{% pullquote Snot City %}

Paul Hack: Some of your most beautiful games (in my opinion), like Bottle Rockets and Temporality, are what you classify as “music video(games)”. The unfinished Eloi, which is also a literary adaptation (of H.G. Wells’ The Time Machine), also belongs to this category. You’ve even hosted a music video(game) jam. Can you briefly go over your self-imposed rules for these games? Are these a further exploration of player authority?

James: A music video(game) is a game that features a specific song; the rules I’m currently operating with are:

no sounds outside of the selected song

the game must end when the song does

the ending should (ideally) concluded the game in a satisfying way

the game should be made to showcase the song.

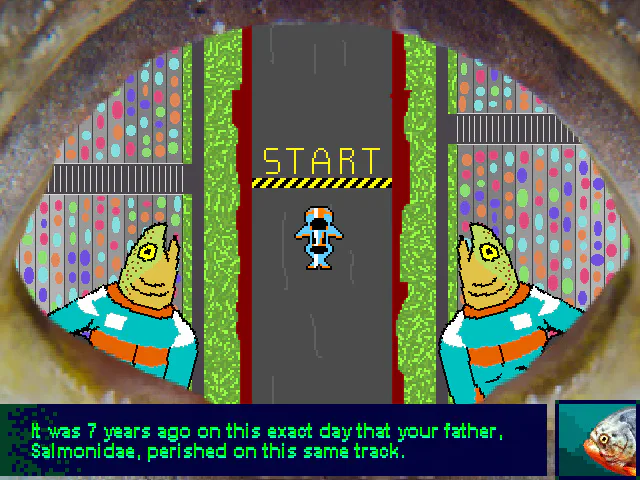

{% pullquote Temporality %}

It originated from the desire to make games with different relationships to the player. Particularly, I was (and am) interested in making games that aren’t as focused on players as most games are: what I’ve been calling non-player-centric games. So, music video(games) continue play on their own, regardless of what the player does. It felt more natural and real than most other games. The world has never stopped for a single human (although my heart stops every time I see one of those dang spiny cockroaches).

Because they don’t focus on the player, they allow the experience to evolve with the music. They are more homages to the featured songs than anything. Eventually, I would love to make non-player-centric games that feature much more than music. In this way, they are kind of an exploration of authority.

The interesting part is that, as much as they take away authority during play, I’ve been told that these are extremely accessible games. A friend told me that their mom doesn’t like videogames, but loved playing You Don’t Know the Half of It: Fins of the Father, particularly because it doesn’t require her to be game-literate to play. I’d be down for a future where anyone can enjoy the same interactive digital experience, regardless of skill. And a future where my home is free of spiny cockroaches.

{% pullquote You Don’t Know the Half of It: Fins of the Father %}

Paul: Are you going to finish Eloi?

James: I hope to finish Eloi someday. I think it’s the prettiest game I’ve worked on. Tight narrative, great source material, no monstrous spiked bugs. Maybe I make all these subversion authority-questioning games as a way to forget and vent about these clanking abominations, if even just for a brief moment. I looked it up, and supposedly this species went “extinct” as of 1000 BC or something. Which is total bull as I can clearly see one trotting around right now.

They’re too armored to kill. I just try to shoo them out my front door when they emerge from whatever hell nest they live in. I mean, most of them are gone now. I’m just afraid to walk around in the dark. Those spines can cut real bad if you step on one. I just want some control over my life ya know?

{% pullquote Eloi %}

Paul: As do we all. What’s the most complete expression of your vision so far? With which of your games are you most pleased?

James: It’s hard to say! Right now, I really love You Don’t Know the Half of It: Fins of the Father and Temporality, especially when they are contrasted: both music video(games), but extremely different. I’m hoping to get Temporality into a conference or an art show. I’d love to see it projected on a wall. It’s much more of an art installation than a typical game. We’ll see how they hold up to time.

Outside of those two, I cried a little while making Bottle Rockets. I’m glad the emotional energy I felt while making it carried through to the players. I do really want to complete the remake of it though; fix that platforming mess. And Don’t Kill the Cow is great too. It has probably the clearest, most concise message of all 60+ of my games.

{% pullquote Bottle Rockets %}

For the most complete expressions, I think I can narrow it down to two: For most silly and fun game, EnviroGolf is my favorite. It went all the way to EGX in London, which was amazing for Joe and me. We had no expectations while making it, so when it blew up thanks to Kotaku, it had already exceeded our hopes.

For most serious/walking-simulator game, An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge is my favorite. It won Silver at Serious Games Conference, Most Meaningful Game at Meaningful Play Conference, and was part of an arcade at the Smithsonian. It’s also the most complex game I’ve made with regard to critical videogame theory.

And Eloi will be my favorite when it’s completed. It feels like a rite-of-passage game. I did a lot of stuff in it that I couldn’t do when I first started making games. For instance, in An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge, your character leaves the water at a point when a tree just ever so perfectly covers him. This was done so I wouldn’t have to make an animation of him standing up to leave the water. In Eloi, I made that animation. And it is beautiful and glorious.

But don’t tell my other games that.

{% pullquote Eloi %}

Paul: Do you have any desire to make something like a SHMUP or a brick breaker, or a straightforward game in some other classic genre?

James: I’ve considered making a shump; the idea is buried in one of my design journals. Usually I write down snippets of ideas as they come, and eventually a few of them congeal together into a complete design. It’s the same approach I took to writing short fiction and film scripts.

It also works well for collaborations. Bringing a snippet of a design idea to the table provides a foundation for nice collaborating. Most of my collaborations have been online recently. I suspect it’s because no one wants to come over any more. I’ve already vented enough about my insect problem, though.

I’m not sure if I’ll ever make a straightforward game of any genre. I have a few ideas for RPGs and freemium/mobile games; they’re all alternative in design of course. You should always question the conventions of a genre before you start making a game in it. Ask if each component of that genre really helps your design. If not, cut it. You’ll have a more elegant game afterwards.

{% pullquote The Duck Game %}

Once my 100 games in 5 years challenge is over, I will start making longer more commercial oriented games (if I don’t start sooner). I suspect they’ll be a tad more conventional than the games I make now, but I do plan on always incorporating critical design and meaningful play.

I like to think of all these freeware games as living reminders of areas that can be explored further. There are already some plans for the spiritual successors of Don’t Kill the Cow and Cat Licker.

And that’s where we’ll leave off for now. Join us in 1 week for the second, concluding part of this interview!

UPDATE: Read Part 2 here.

19 comments