Hey! This is PART 2 of a really long interview. Before you read this, make sure to read PART 1 first!

Thanks for coming back! Join me as we continue probing the mind of James Cox, picking up from precisely where we left off last week…

{% pullquote You Don’t Know the Half of It: Fins of the Father %}

Paul Hack: A bunch of your games are the products of various game jams. Other than being a good way to supplement your progress towards your 100 game goal, what do you get out of jams? And what have you learned from jamming?

James Earl Cox III: Game jams are wonderful safe spaces to fail. Most of the jam games I’ve created are out of my comfort zone in one way or another, almost always in a way that could end in failure, especially since the design is crafted on the spot. Because jams have themes and constraints, it’s hard to jump in with a design idea in mind. And as some jams don’t allow you to use premade assets, jams become whirlwinds of development: design, art, code, sounds, trouble-shooting, playtesting, release; all within that condensed period of time. There’s so much happening so fast that you have to be ok with failure.

The other facet I love about jams is how often they’re tied into current events. CandyJam, Women are Too Hard to Animate Jam (or WATHTAJam), and the recent JamForLeelah are three good examples. It’s a proactive way to spread awareness about important topics while creating.

Game jamming is excellent for learning how to experiment. You don’t get that much time during a jam, so you have to allocate your resources wisely. Understanding that there aren’t enough hours to make something huge or extremely polished, I aim for unique when jamming; creating a game that uses the theme in an interesting and unexpected way. You usually only have a day or two, so don’t expect a masterpiece. Rather, aim for something quirky and weird. After the jam, you’ll be able to see how people react to it. If they love it, then you can expand it. If they hate it, then no worries! You only spent a few days working with that idea.

{% pullquote Murder Clown %}

Paul: You’ve also organized a few game jams yourself, like the music video(game) jam we touched on earlier. One really interesting project of yours is the series of Clone Jams. Tell me about your intentions with those.

James: The CloneJam series came together quite swiftly. Back when Game Jolt first released their game jam system, I was looking for some way to celebrate all the people in freeware. Not just the larger figures, but past freeware creators and the up and coming as well. So when I read that Game Jolt’s jam feature was now live, I jumped on the opportunity to make this jam series. It also felt like a great way to open communication between budding developers and established ones.

Since then, many freeware developers have been added to the growing list. We’ve had #CloneJamPorpi featuring Porpentine, #CloneJamJake with Jake Clover, as well as #CloneJamCactus with Cactusquid. I’m hoping to see if Terry Cavanaugh, Anna Anthropy, and Notch would like to be included as well. Something important to note is that every featured developer has given their consent to be a part of CloneJam. Because the series is meant to be a fun celebration, it wouldn’t make much sense if the featured artist was unaware or didn’t want to be included. They’re excited to be a part of the jam as much as the participants.

My hope for the CloneJam series is to encourage game creators to experiment in the featured developer’s style, and to reinforce that we’re a community of encouraging welcoming creators. It’s a safe outlet to try your hand with unfamiliar subject matters, styles, and themes, while also showing support for the featured developer: win win!

As of now, the CloneJam series will continue on at least until August. I’m always on the lookout for more developers to feature as well, so I could easily see it continuing living on farther than that.

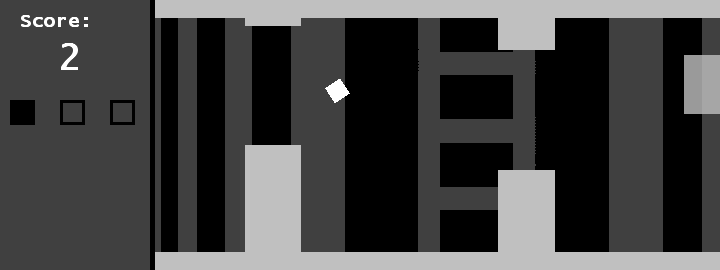

{% pullquote Hover Cube %}

Paul: I realize the Clone Jams are more about paying tribute and capturing a style than about making literal clones, but don’t clones serve a purpose? Aren’t new genres carved out largely by clones—and by iterations and incremental embellishments of a single original idea? And aren’t clones a natural byproduct of every medium?

James: Clones do serve a purpose and help further genres; if a game is cloned a number of times, we can assume the origin game must have some draw to it. An issue I have with clones is that when they number enough to create a genre, then players will expect certain conventions to hold true within those games. If you subvert those conventions then players may not enjoy your game, even if your different use of mechanics/plot/art is genius.

As laid out in their GDC 2014 talk on interpreting feedback, Monaco: What’s Yours Is Mine was pitched as a stealth game initially, but players got upset that they couldn’t ghost levels. Although Monaco is an amazing game, players couldn’t shake the genre convention idea that they should be able to beat a level without ever being seen by an NPC. So Pocketwatch Games had to re-pitch the game to avoid the audience trying to play it as a stealth game.

The easy way around this is for us all to make games with so many different styles, mechanics, and art that players have to approach games with an open mind from the get-go. Eventually, and hopefully, no game will be judged based on a genre; they will be enjoyed for the experiences they are, and not interpreted as ones they’re not.

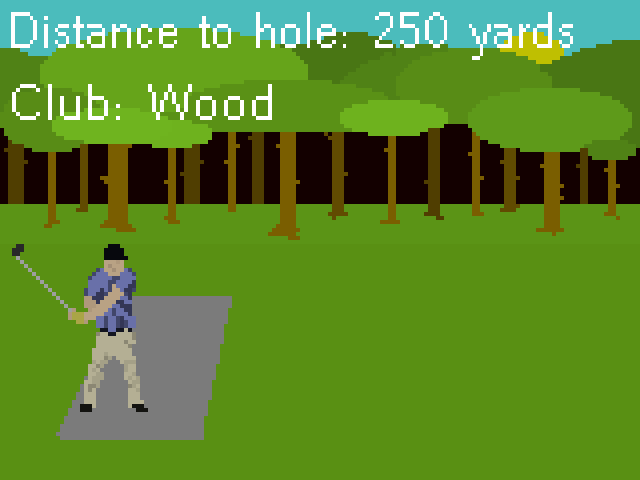

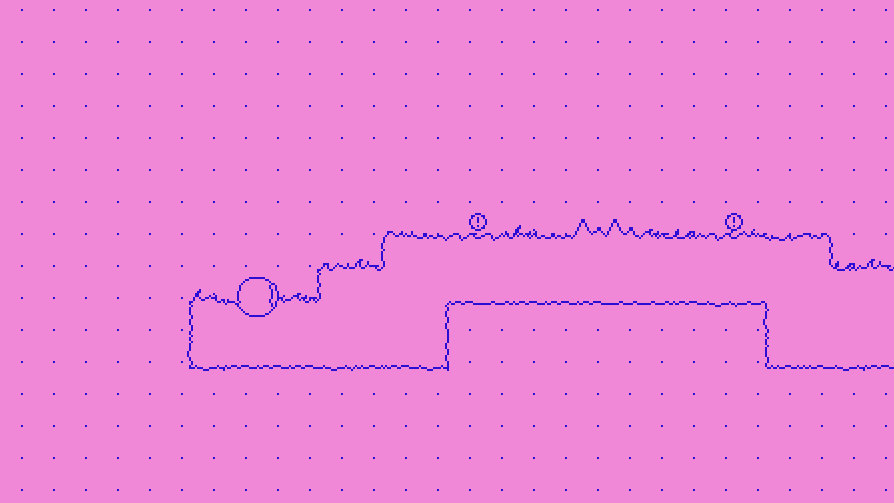

Paul: Let me ask about a specific game of yours. I adore EnviroGolf, and I know I’m not alone. In fact, it turned out to be a lot more successful than you ever expected it to be while you were making it. Can you tell me how EnviroGolf came to be?

{% pullquote EnviroGolf %}

James: Oh jeez. EnviroGolf. EnviroGolf is a strange little beast, isn’t it? Well, EnviroGolf is a hideous chimera that Joe and I came up with. We usually have several running jokes about various game ideas, and this was one that just spiraled so out of control that it became real.

So it kind of went like this:

Joe and I didn’t really enjoy sports videogames. We were in that camp of people who think you should go outside and play a sport if you really wanted to play it. Usually when one of us spouted our opinions on the topic, someone in the room would point out that it was cold and snowy outside, or that they had a broken leg and couldn’t very well play. We didn’t care though, that person probably played sports games and sports games cloud judgment.

Sports games are fun because of the power involved. Players like the simulation of playing the sport; that feeling of hitting the ball back, or nailing the power meter bar right at the top. So our first instinct was to completely disregard that. We needed to make sure our game had no simulated sports-fueled power; this lead us to joking about a text-based sports game.

The second element was how sports games usually never address anything deeper or greater than the sport. It’d be counter-intuitive to play a sports game that dealt with financial stability or government politics. So we had to add something like that in; even better, a message that completely conflicts with the gameplay itself.

{% pullquote EnviroGolf %}

We ended up with this running joke about a text-based environmental oriented golf game. First it began with jokes about the types of things it might say to the player. Or what the end score would be. Then we started doodling out images for it, or mock-ups for the interface.

The game took us two weeks to make, but in reality, we maybe spent four actual days working on it. It wasn’t a very serious production cycle. I’m pretty sure throughout development, we both kind of did our parts in a sarcastic way. Jokingly creating the game, half-daring each other to continue. None of the facts within the game are real, and the power of the clubs was researched in about 15 minutes on Google. So it was completed and I put it up online.

The next day we found out that EnviroGolf had made it onto Kotaku.

Now we love sports games. Not Madden or what-have-you, but sports games with these twists. We have a couple more planned for when my 100 games in 5 years is over. There is just so much unexplored room in sports games for weird and alternative play. Out of any genre, it seems like sports games are the most stuck in their genre that they become the most open for amazing mutations.

The new joke that Joe, a few friends, and I have running is about all these extremely open world games. Usually when one of us starts pitching a bad game idea, another one of us will offer the suggestion: “Oh! That sounds great! But what if, now stay with me on this, what if we make a game that’s like a pixelated Mass Effect, with millions of planets, and you can do anything you want.”

I doubt this joke will ever turn into an actual game, and if we did start working on it, I’m pretty sure I’d die of old age before it’s released.

{% pullquote Respire %}

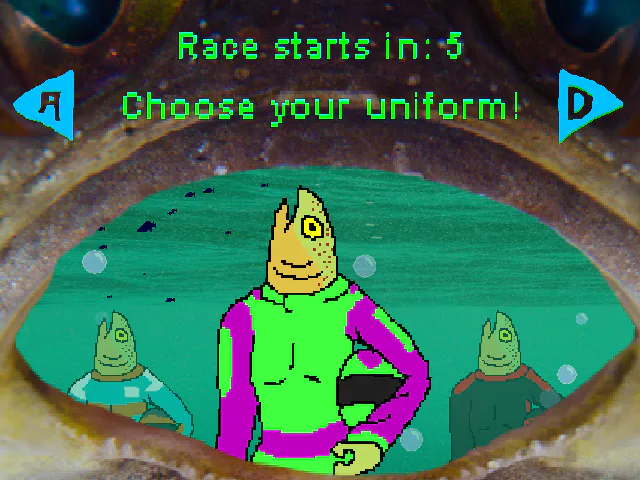

Paul: Let’s digress into something more practical for a moment. What tools do you generally use to make your digital art?

James: For pixel art, I actually use the built-in GameMaker sprite editor. It retains hard edges when you scale up and down your images, so there’s no worry about interpolation or blurring. It also offers a nice feature where you can watch your sprite’s animation play at varying speeds.

When it comes to non-pixel art, I stick with Photoshop. GameMaker freaks out with art when it’s too big, and Photoshop has a lot of nice features that GameMaker doesn’t.

Joe uses MSPaint. So all of the art in EnviroGolf, the fish horses and fish eagles in You Don’t Know the Half of It: Fins of the Father, and all the characters in Garugol: Lord of Shadows, Executively Appointed Arch Duke of the Pyramid Realm (to name a few of his arts), that was all made in MSPaint.

For sound editing, I use Audacity, and Joe uses Ableton.

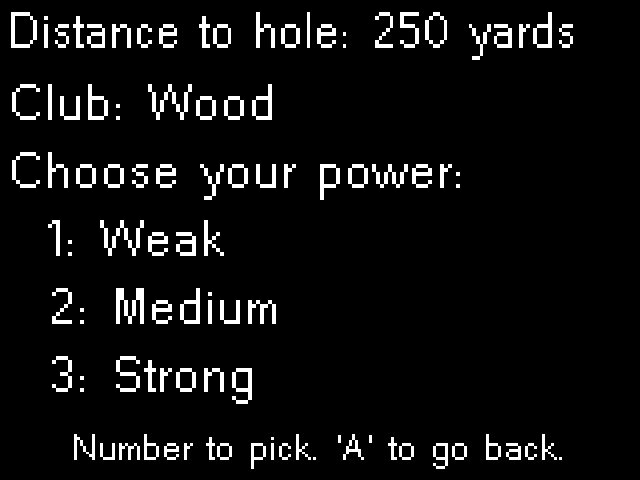

Paul: In a few of your games, you’ve experimented with visuals constructed from tangible materials. Both Respire, a lovely music video(game) about a haunted spaceship, and the even-more-experimental-than-usual Ten Stories Up Elevator use a striking paper cutout aesthetic. What inspired these and will you use this technique again?

{% pullquote Ten Stories Up Elevator %}

James: I’ve been trying to break away from pixel art for a while. Not fully, as there is always a time and a place, but just to broaden the art I use in games. Jack King-Spooner and TheCatamites were both huge inspirations for using tangible art. It’s a style that feels a bit more welcoming and homely, warm even. Jake Clover’s art is also inspirational.

In terms of Respire, I wanted to make a game where I could leave the little scanned artifacts in the game; those hanging chads that don’t get cropped out when you clean an image. They work wonderfully for space debris. Ten Stories Up Elevator needed a sense of curiosity that handcrafted art satisfied completely.

I hope to use that style again in future games. I always have a ton of cardboard laying around for big projects. If everything works out, I’d love to make some games using other found objects as well. Sock puppets and finger paints even. It really comes down to the game’s tone and mood though. Snot City wouldn’t have worked with any art other than hand-drawn, and I’m not sure if EnviroGolf would have had the same reception had its art been hand crafted.

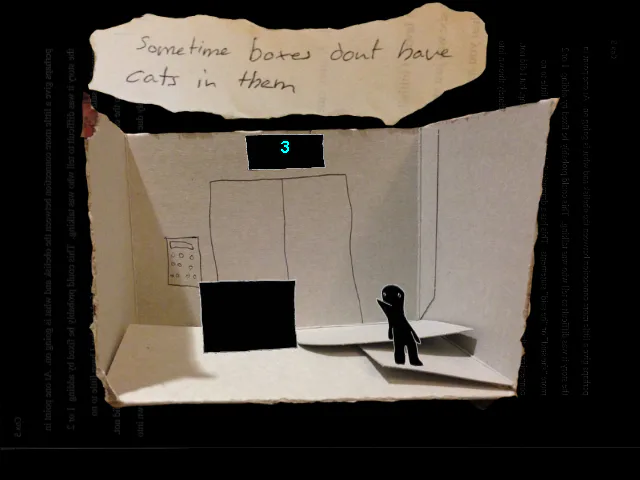

Paul: DarkWhite is an early game of yours that has its own unique visual style not repeated in any other of your games. Was that all pen and ink drawings?

{% pullquote DarkWhite %}

James: It is indeed all pen and ink! Considering how little content there is in DarkWhite, it’s received a ton of generous feedback complementing the art. 3 Blind Mice: A Remediation Game for Improper Children is a combination of pen and ink with watercolor. But I think what really makes DarkWhite pop is the parallax and depth to it. How the characters pop in this comic-book-esque world.

I’d love to make more games in that style and plan on it too! Just a matter of what game and when.

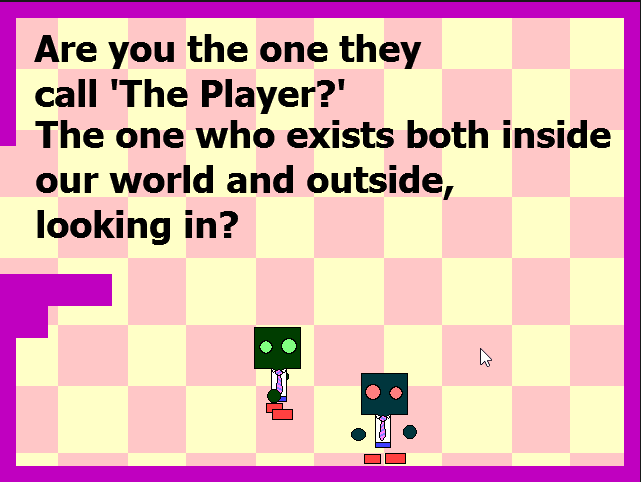

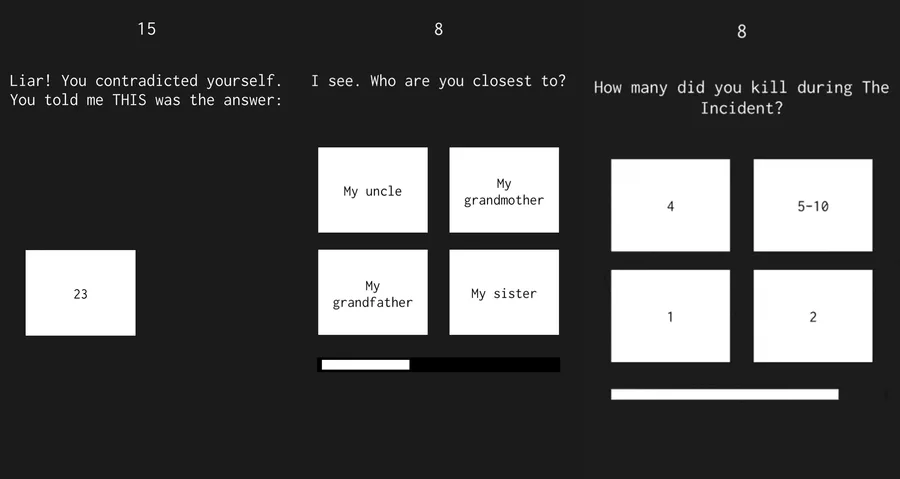

Paul: There’s one more semi-scholarly type of thing I want to ask you about. You wrote a good article about a topic that fascinates me: metafiction; specifically, you wrote about how a few metafictional techniques can be applied to games. You also made a cool little game that illustrates the points made in the article. What’s your favorite metafictional content in a game?

James: Metafiction is fantastic! There is so much room for growth in games with metafiction. I think my favorite metafictional content in a videogame has to be in Tom Clancy’s EndWar. The game is an RTS where the player controls units using their microphone from a commander’s point of view. The key words it uses sound perfect for the tactical scenarios you engage in: “Squad 2, move to delta.” “Squad 7, attack hostile 1.” It feels great when a game is able to get you into the role of a commander, mentally and physically; the game makes use of your role as player to replicate the role of a commander in a control room, issuing commands far from the battle in an isolated location.

{% pullquote Metafiction Game %}

The Stanly Parable also comes straight to mind when discussing metafiction; it reveals itself as a game, it immerses the player into it with metafiction. It’d be a bit hard to avoid metafiction when making a game that is all about dissecting what a game is. If you haven’t played The Stanley Parable, you really should. It’s a wonderfully accessible experience.

And lastly, the first Assassin’s Creed has some neat pseudo-metafictional moments. Not quite metafiction, but because your character is plugged into a machine, the glitches and boundaries that prevent you from exploring the city feel natural: they’re artifacts of being in a simulation. That fictional narrative makes all game anomalies believable and narratively motivated. I remember when I encountered a glitch in the game, I thought it was meant to be a glitch in the simulation, not an actual issue with the game. Which is an amazing feat all developers should strive for!

Just imagine how amazing it would be if games used the right amount of metafiction, so that when you play them, even if you encounter a bug, it doesn’t pull you out of the experience. And if games were able to naturalize pause screens and HUDs to be a part of the internal universe. I think metafiction is our best chance at creating fully believable immersive worlds. Assuming you’re into that kind of cyberpunk future.

{% pullquote 3 Blind Mice %}

Paul: Two of your games, 3 Blind Mice and Mr. Kitty Saves the World, stand out to me as good examples of strong metagame content—and by that I mean the stuff you play, or play along with, when you’re not actually playing the game. For example, 3 Blind Mice is subtitled “A Remediation Game for Improper Children”, and part of the fun of it is pretending to buy into the conceit that you are a strong-willed child in some near-future dystopia being forced to play this “game”.

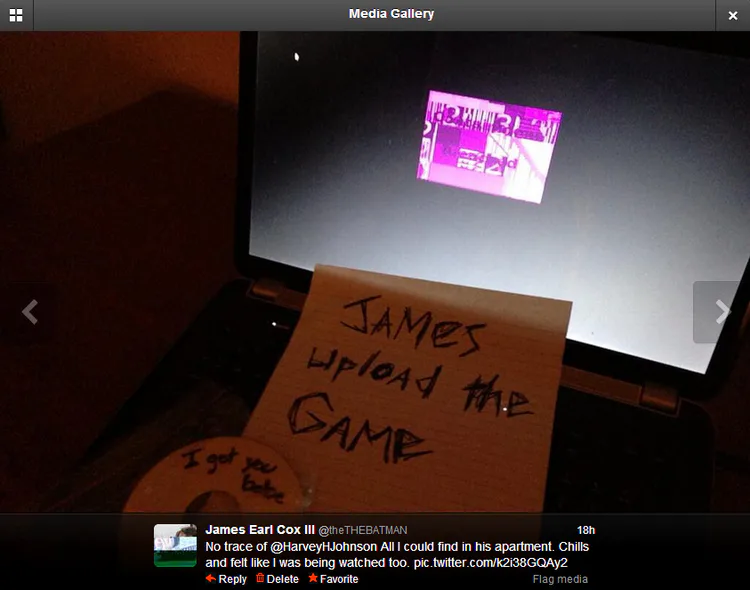

Mr. Kitty is perhaps a more sensitive topic but… well, perhaps the most interesting thing about it is its creepypasta-like backstory. Is it possible/advisable/fun for a developer (or writer, filmmaker, whatever) to effectively use story elements that are not actually provided as part of the main work?

James: It would be great if more developers incorporated strong immersive metafiction in their videogames. We haven’t seen a lot of it just because that sort of world play can be hard in videogames, unlike in films and novels. The Blair Witch Project is a great example of a “found artifact” film. How the film itself is meant to be the end product of a series of real world happenings. That movie works well as filming can appear rather passive: turn on the camera and you’re making a film. Of course filming isn’t passive, it takes a lot of energy and effort. But for creating this found artifact feel, you can get away with more in film.

Books are a bit more active on the creator side as it requires someone to sit down and write it out. A lot of metafictional books are written as reflections of the fictional author’s past. But for games, you have to somehow incorporate the fact that it’s a videogame. Not many people would go into the woods and see a ghost and think “oh man, I better make a game or this ghost will eat me.”

Not that we shouldn’t try to make such videogames! You just need to set up your game in such a way that the audience is willing to play along. Make it fit into reality somehow. Alternate reality games (ARGs), are fascinating in how they can blur reality and fiction, yet they most often aren’t videogames and are rather temporal. For a good example of an ARG, look up I Love Bees, the Halo ARG.

{% pullquote Mr. Kitty Saves the World %}

As for Mr. Kitty Saves the World, I’ll forever regret uploading that horrible thing. I’m sorry that it’s affected so many people. I should have been strong like Harvey. I shouldn’t have given in to them.

Paul: I assume you somehow make time to play at least a few indie games. Who’s hitting it out of the park right now for you?

James: Monument Valley is pretty spectacular. I often wander the levels when I’m waiting around for events to happen.

In terms of PC games, I’m hoping to try out Donut County at GDC this year. I also had the pleasure of playtesting Hyper Light Drifter and can say that it’s as juicy and fun as ever.

The most recent game I’ve dived into was Space Station Silicon Valley for the Nintendo 64. It’s a terrific game and everyone should play it to completion. That and Iggy’s Reckin’ Balls. If you don’t base your every design decision off the question: “would this work in Iggy’s Reckin’ Balls?” then your game is probably garbage and you need to play more Iggy’s Reckin’ Balls.

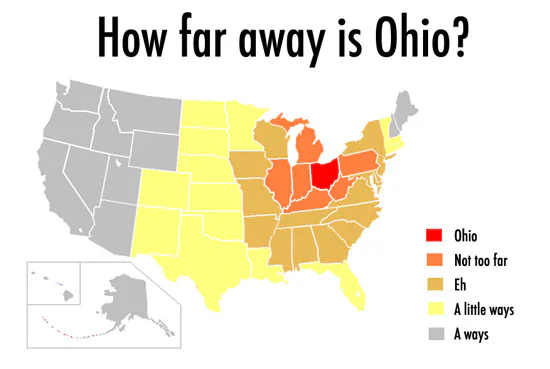

Paul: Before I move on to asking about your analog game creations, can you tell me about this hugely ambitious cycle of Ohio-based video games you’re planning?

{% pullquote Ohio, Ohio concept art %}

James: Joe and I are working on this game series, our first commercial games if not close to it, set in Ohio. We’re calling the series as a whole “Ohio, Ohio”. Thirteen small narrative games, each set in their own Ohio towns: “town-name, Ohio.” The name of the first game is “Purgatory, Ohio.”

Ohio is a fun state. Did you know that 24 astronauts came from Ohio, including John Glenn and Neil Armstrong? So did Steven Spielberg, LeBron James, and Ted Turner. A lot of great people come from Ohio.

Both Joe and I attended University in Ohio. Joe is still attending University in Ohio, at Ohio University. Not to be confused with Ohio State University. Ohio University is located in Athens, Ohio. Not to be confused with Athens, Greece. I went to Miami University of Ohio for my undergraduate degrees, not to be confused with Miami, Florida. Miami of Ohio is located in Oxford, Ohio. Not Oxford, Florida, or just Oxford, England.

Did you know Orville and Wilbur Wright lived in Ohio? People debate if the birth of aviation belongs to Ohio (where they lived) or North Carolina (where they tested their flyer).

{% youtube _eMb_kh_glw %}

We jokingly say these Ohio games are self-therapeutic; our way of expressing our experiences with the state. Which is both a truth and a lie. The real Ohio doesn’t have ogres or FloorMart, but the games do contain anecdotes we heard and experienced in Ohio.

I’ve been told “Ohio is a fine state to be from” by more than one person, in more than one state that isn’t Ohio. Ambrose Bierce, the author of “An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge” is from Ohio. I didn’t pick his story to translate based on that fact. It just happened. Ohio catches up to you. You never really leave Ohio.

Ohio, Ohio is a reflection of that. Each game goes somewhere, yet it goes nowhere. You’ll play these games at your computer, and when you finish them, you’ll still be at your computer. Ohio can feel like that.

Paul: You’ve designed a few live-action games. Indiecade calls them “Big Games” and some might even call them sports. First of all, what’s the difference between a game and a sport, do you think?

James: That’s a good question. I think the difference might be a bit arbitrary. All sports are games to begin with, but for a game to be a sport? You’d think it has to do with rules or money or the players. But none of those elements are particularly unique to sports over other games. Maybe it has to do with the advertising budget, or the participants’ funny looking uniforms?

League of Legends is recognized as a sport by the US government and their uniforms aren’t so zany, so perhaps it’s up to the audience.

If you can imagine your sports uncle sitting in a mancave enthused by a game of it, then it’s a sport. If you imagine ‘em sitting in there scratching his head, then it’s not a sport.

{% pullquote HermiTug %}

Paul: Will you give me a brief overview of this game you made with your brother Joe, HermiTug?

James: Hermitug! Hermitug is an amazing game to play. You wear laundry baskets on your back and fight over a sack of laundry and it’s boundless hermit fun!

For a bit more context: This is a big field game, 100% analog, no computers involved.

To play, you’ll need two teams of 4 or 5 players. Each one of you wears a laundry basket on your back; if it falls off or is knocked off, you sit inside of it and can’t move. In the middle of the field is a laundry bag full of stuff (the more stuff and the heavier the better). There are two ways to win: you either knock all of the laundry baskets off of your opponents’ backs, or you drag the laundry bag to your team’s side. The one caveat is that if your laundry basket is knocked off, although you can’t move, you can still flip baskets off of the backs around you.

It’s a wonderfully simple and fun game! Unfortunately, we don’t have any pictures of it in action yet, but we do have advice: make sure to wear gloves and knee pads. Especially if you play on a non-grassy surface.

If you’d like to play, the official rules are on http://seeminglypointless.com/hermitug/. And if you do decide to give it a go, I’d love to see some pictures; just tag me on twitter!

{% pullquote Kill the Kraken %}

Paul: At Indiecade 2014, I had the awesome pleasure of playing your team-based romp Kill the Kraken. I think I enjoyed being one of the kraken’s tentacles best. How did you come up with this game and what was the development process like?

James: Kill the Kraken is closely related to Humans vs Zombies, yet rather than pitting humans against hordes, it pits humans against one giant monster. The idea was inspired by Humans vs Zombies, and informed by my prior experience running HvZ at Miami of Ohio. I wanted to create an experience that condensed the chaos of HvZ into a short burst of action.

The asymmetric teams make the game fascinating for more than one go, but I find that it’s in constant need of testing as players’ different strategies reveal different strengths and weaknesses. The largest downside of the game is the somewhat lengthy set-up time. Collecting all of the sock ammo, restocking the bases. Kill the Kraken was a valuable lesson about limiting the equipment required for big physical games. Both in terms of set-up and transportation.

Kill the Kraken had a really strange development process. The game idea was shaped during the final months of my role running Humans vs Zombies. Yet the physical game didn’t come together until the filming of a certain llama focused horror movie. Our first playtest was with the actors and crew in the film. From there, it was submitted to Come Out & Play.

{% pullquote Kill the Kraken %}

Paul: Do you have any other live-action games in the works?

James: Several, in fact! The one closest to fruition is named Australia Repopulates the World: The Game. In terms of play, without giving away the game, think big speed Risk.

If all works out well, this game should see the light of day in late March. My collaborative partners and I have a blast working on it, and the playtests have all been amazingly smooth.

Paul: There’s another fun subset of your game design work that bears mentioning: your drinking games! You’ve made one to play while watching the “film” Birdemic, one that’s played while listening to “Roxanne” by The Police, and another that you play while playing FTL. You’ve even worked out rules for a game where you basically get drunk and make a movie, called Drunk Script, though I don’t know if that one’s actually been… playtested yet. Has it?

There’s a lot of potential in drinking games, in both reshaping old media into interactive comradery and in gamifying processes.

James: The fantastic element about drinking games is how you can transform almost any passive activity into an active game through a few simple drinking rules. Or how you can turn a single player videogame into a multiplayer game without modifying any code.

You have a few friends over, maybe one of them wants to play FTL. It’s sadly a single player game. But guess what? Now you have a silly extra layer of interaction to make the game inclusive for the crowd!

These kind of additional inclusive rules can extend far beyond FTL. I’d love to play a drinking game to Alien: Isolation. Or even a Starcraft one. I heard that there is a round-robin style Binding of Isaac drinking game; that sounds like a blast.

The Birdemic drinking game turns the film into a competition. Team bird or team human? The outcome is always set, but you can’t take a film like Birdemic seriously. Joe actually made the “Roxanne” drinking game. It’s a satire on linear media drinking games, how the drinking beats are obvious from the get-go; like Candy Land but as a drinking game.

{% pullquote I’m a Little Teapot %}

For the Drunk Script, it has indeed been playtested! The scripting, the filming, and the editing. Rob Horn and I were hoping to run another session with a new set of participants before we launched any media pertaining to the project. There’s a lot of potential in drinking games, in both reshaping old media into interactive comradery and in gamifying processes.

Paul: What is the future of drinking games?

James: The future of drinking games? Chicken Juice. The new hot folk drinking game on the block. Within ten years from now, it will be played across the nation. No one will remember who made it, but when a porch of youngsters flip cards in the heavy night and chant out “Chicken Juice!” we’ll hear, and we’ll know who made it.

Paul: James, I have but one more question. It’s an open secret that you’ve stashed a few hidden games around the web. Will you give me a hint for finding one?

James: The best secrets are hidden in plain sight. Good luck!

Paul: Thank you so much for all the time and thought you’ve given this. I’ll be on the lookout for whatever you release next!

{% pullquote Mr. Kitty Saves the World %}

1 comment