And then I came to Three ways,

And each was mine to choose;

For all of them were free ways,

To take or to refuse.

Major choices in narrative games are often expected. Of course your decisions will have an impact! That’s why you play games after all: to see an immediate and lasting consequence to your actions; to shape the world in the mould of your heroes; to decide who lives and who dies!

Giving my players choices was always my intention, but my game’s themes aren’t so grandiose.

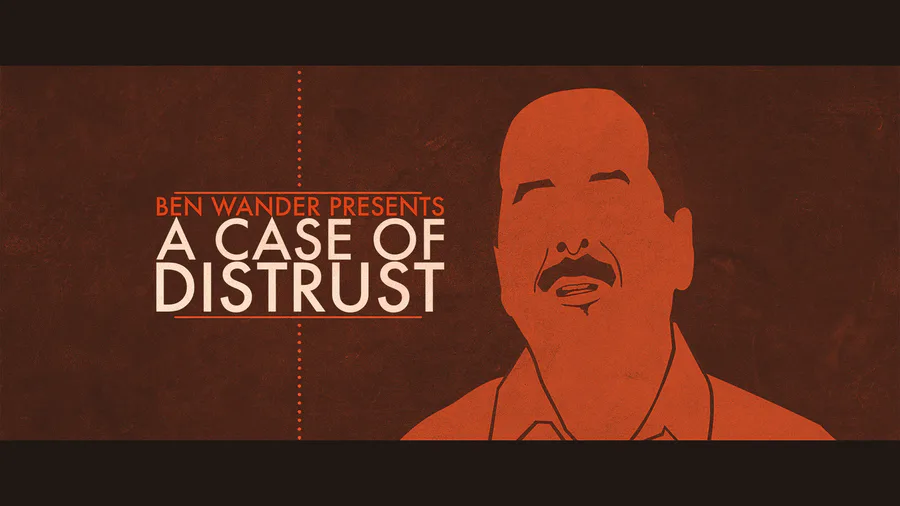

A Case of Distrust is not an epic. You won’t find mythical creatures or magical spells between its covers. It’s not about transforming the world, or saving it from the grasp of evil. It’s about a society, its charm, and its blemishes. It’s about understanding the impact of an average person, and how little that can actually be. It’s about a mystery with a culprit — one character has to be guilty, and, whatever a detective’s choices, that fact won’t change.

So what do players decide then?

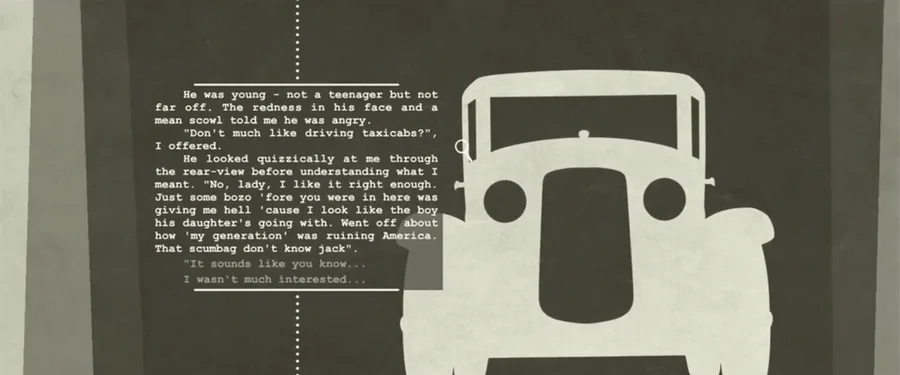

They choose how to navigate this society. They dictate their main character’s reactions. They build the Phyllis Malone they want to see.

Of course, a personality has personal consequences. The world won’t be different tomorrow if you’re more friendly to your neighbour — but your neighbour might be nicer to you! Depending on Malone’s actions, characters will start to see her in different ways. Sometimes that will mean an easier time solving a mystery, while other times it might add to her difficulties.

That’s what I’m working on now. The reactions of characters based on my players’ decisions. The subtle changes in the mystery based on who you think Malone should be.

Choices that won’t redefine your world. But choices that are intimate.

Quote from The Choice by Robert William Service

Top image by I. Melenchon

2 comments