For the past four years, I’ve been working towards creating and releasing 100 games in 5 years. My current count is 80, and as of writing this, I have a little under a year left. The challenge began in June 2012, and will end June 2017. At my current pace, I will need to make 2.5 games a month to reach this goal. Of the 80 games I’ve made and released, about 10 of them are hidden around the web as experiments, games I can’t attribute authorship to without spoiling the experience. 9 of them are non-digital games, and 3 of them are released class projects.

The other 58 are short-form digital games, and even though they are small, they have garnered attention, receiving Media Choice at IndieCade, showing in the National Art Center Tokyo alongside OK Go’s I Won’t Let You Down (both Jury Selects in the Japan Media Arts Festival), receiving multiple awards from conferences such as Serious Play, and showing in Indie Areas at events including EGX and Tokyo Game Show. Even with 20 games left, I’ve leaned a lot in pursuit of this goal. Currently, I cannot recommend this challenge (5 years is a long time and making 100 games is a huge commitment), but I can share what I’ve experienced: from the creative work flow I’ve developed through making 80 games, to how my interests and design instincts have shifted, to what I’ve learned from such a lofty goal.

Here, I lay out what my plans are for releasing further writings and what they will be. Then I provide some numbers from this journey so far, share some of the ways this challenge has shaped me, and conclude with one lesson I’ve learned.

The ‘Game Plan’ for Writing

I wanted to write a single post about the final leg of this journey: how I feel now that I’m so close, the lessons I’ve learned through these 4 years, tips and tricks of this development style, and so on. But there is too much to cover in just one go, and while everything I’ve gained is related to game development, it’s too disparate to fit into a single entry. The simplest solution? I’m separating it into different manageable posts, each covering a different topic. This way, they’ll be condensed into readable chunks, and everyone can glean the pieces relevant to them, while skipping the irrelevant.

Writings to be released in the remainder of 2016 and throughout 2017.

• Rules of the Game: Why We All Need Our Own Working Definition of ‘Game’

• Drag and Dropping Games into Existence

• We Have to Get Serious about Games

• Intermedia Translation Games

• Coping with Blank Canvas Syndrome

• Work Flow in a Marathon of Sprints

• I Play, Therefore I Make: The Unhealthy View of Playing as Making

• Love Short Games: Why Short Games are More Important Than We Know

• Every Display, an Installation

• Burn Out: More a Sleep than a Lightning Strike

• Music Video(games) and Low Performance-Anxiety Play

• Creativity and Constraints: How Time Limits, Stripping Down, and Dumb Code Can Make Good Games

I recently posted Intermedia Translation Games. It’s placement as fourth on the list is because these pieces won’t be released in any particular order. Some that I start writing earlier may take longer to flesh out, research, organize. However, once any of them are published, this article will be updated with the appropriate hyperlink. Another way to stay updated: I post updates on my site, Just404it.com, and on my twitter, @just404it ![]() , when I release games and writing. Ultimately, once the 100th game is complete, a post-mortem of the challenge will be set free on the web.

, when I release games and writing. Ultimately, once the 100th game is complete, a post-mortem of the challenge will be set free on the web.

At this stage, I’ve already published a few musings on games: from research on metafiction in videogames to a call for more unique fantasy to a mid-challenge write up.

A question I’ve asked myself while writing these is “how does making 100 games in 5 years pertain to ____?” The simplest answer: it affects everything. By creating so many games in such a condensed period of time, I’m constantly confronted by all manners of thoughts that occur during any given development cycle. My trip digit goal has shaped and informed the way I view games: playing them, making them, analyzing them. It’s changed the elements I appreciate in games, and it’s given me strong opinions. Opinions both supported and opinions shifted by this experience.

Some Numbers

Table 1: The number of games made each year; how many conference selections (based on how many games were displayed at conferences, festivals, and expos), how many awards my games received, and how many talks I’ve given.

Year | Games | Conference Selections | Awards | Podium Presentations, Lectures, and Panels

2012 | 11 | 2 | 0 | 0

2013 | 17 | 5 | 1 | 0

2014 | 34 | 11 | 5* | 1

2015 | 11 | 12 | 1 | 3

2016 | 7 | 15 | 1 | 5

Total: | 80 | 45 | 8 | 9

2 of the 2014 awards were “Game of the Year” and “Best Digital Game” by my undergraduate alma mater Miami University of Ohio.

Divining the Numbers

As seen above, 2014 was my best year for game output, while 2016 was the best for conference selection. Also apparent is the drop between 2014 and 2016. The reason is burning out. What did I expect from making 34 games in a year? Something I’m perpetually recovering from and building supports to prevent from happening again.

The Effects of Making 80 Games in 4 Years

In my 2.5 year write up, I speculated about the positives and negatives of this challenge. This time, let’s enter a bit of a grey area. Rather than try to separate the good from the bad, I want to lay out a few effects this goal has had.

Pressure to Produce: Making so many games in this a period of time forces a very release-oriented mindset. One of my rules is that I won’t release a game until it feels complete, so I never feel like I can take the time to make a game to purely learn. I do, however, try to incorporate something new into each of my games. Be it a new piece of code, a new design idea, new art style.

Confidence through Creation: I don’t feel impostor syndrome. This challenge has given me the confidence to believe in myself: I can make games. While I don’t believe I have a defining visual style, I do have a design voice. Continually making games helps reinforce my identity as a creator.

Here’s a Game for That: This challenge produces a lot of games. As such, I have a lot of games to share. For submitting to venues for show, the question changes from “Do I have a game that would fit?” to “Which games fit best?” On the downside, it eats away at deadline motivation. In my first two years of game-making, I could count on a conference submission deadline to help motivate me to finish a project. Now, because I have games to fall back on, deadline motivators don’t work as well as they used to.

Design Confidence: I generally can lay out a game before I ever touch the code. It’s made me very scope-down savvy in my design sensibilities. Not because I’m rushing the process, but because cutting out fluff makes for a stronger design. If any element of a game doesn’t support the central message, I remove it.

Timing Instincts: I can generally gauge how long it’ll take me to build a game. This is half influenced by the fact that I don’t make games that take years to release, and half because I’ve learned how long my process takes. This also discourages me from working on larger projects, even if I could complete them.

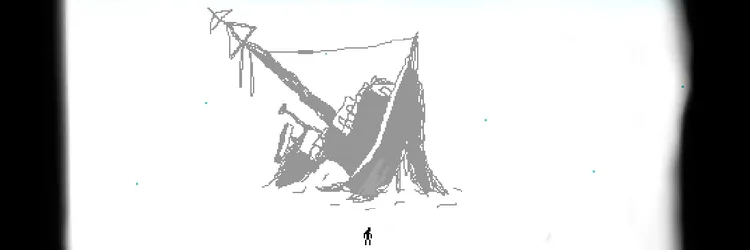

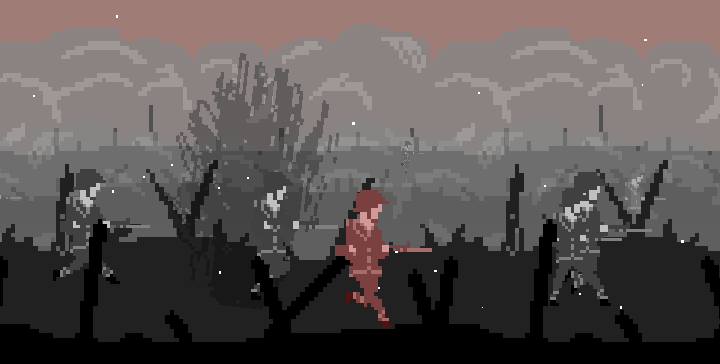

Experimental is Better: For small games, the stranger the game, the better it is. This has held true for both my own exploration and for public reception. If I was to make a Mario clone, it would be just that. When I make an experimental game, I also learn more about my own design sensibilities.

Reception Intuition: Not all of my 80 games are good, not all of them are bad. Having made so many, I can predict early in production which way they’ll go. Even if I get the feeling a game will turn out poorly, I try to complete it and release it anyway. This habit formed because there are occasionally anomalies. These games usually take less than a month to make, so there isn’t much lost time on a bad one. And if it turns out good, then my sensibilities shift.

Time is Not a Savior: If a game doesn’t attract attention, polishing it won’t save it. The games in my 80 that were favorably viewed (both in my eyes and in the publics) executed well within a day or two of development. More so, extra time on a project doesn’t mean it’ll receive more attention. My game Temporality won Silver at Serious Play Conference, was a Jury Select in the National Japan Media and Arts Festival, and was made in 4 days. The game only required four days for me to implement, so I only spent four days on it. On the other hand, I spent 2 months creating RUNNER, and, as of writing this, it has under 200 plays.

A Lesson to be Learned

I need to be ok with doing less. Before I burnt out, I had a structured mental plan for when I wanted to have games completed. This “completion” included having games released and patched. When I fell behind on one project, it would delay others. This cycle was self-perpetuating, delays leading to delays leading to delays. The way I’m overcoming this now is by keeping emergency time. It’s good to have established breaks, even full-on days for just relaxing. It’s also good to keep time open to complete old projects, to handle non-immediate troubles, to catch up on life. Don’t let far-off worries become emergencies; take care of yourself by being proactive.

The Final Year

With 20 games left, and roughly 8 months remaining, I need to make about 2.5 games a month. It may seem like a tall order, especially since 2015 and 2016 lagged. In my favor, I have several old projects I mean to complete and one physical game I need to type the rules up for. Through this challenge, my design voice is solid, I know what I want to make, and I know how to make it. Ultimately, we’ll see how this challenge ends in June 2017, but I’m glad I took it up.

2 comments