This is a postmortem of Mackno Studio’s Space Explorer game, three years later.

At Mackno Studio we are two programmers that one day, in January 2015, we had done a prototype of Space Explorer, don’t know how for sure. I think it was my partner working on the idea of the game for a while, individually, and then he showed it to me.

We sat down, analyze what was built, discuss the ideas behind the prototype and came up with the “brave” decision of continue the development of the game that will keep us busy for the next 6-8 months working part-time, because each of us has a day job to pay the bills.

It’s fair to say that this was our first video game as a video game studio. Previously each one of us had worked in some games, some of them by contracts and some of them in game jams and some of them just for fun.

Once the game development machine got in motion, most things were fluid. The ideas came up as we worked, and soon we had a long list of features to put in, most of which did not end in the game, but hey! That’s how it’s supposed to work, right?

Since we have the prototype built, mostly with programmer art, which was ugly and hurt our eyes, we decided to work from there and not rebuild everything from the scratch.

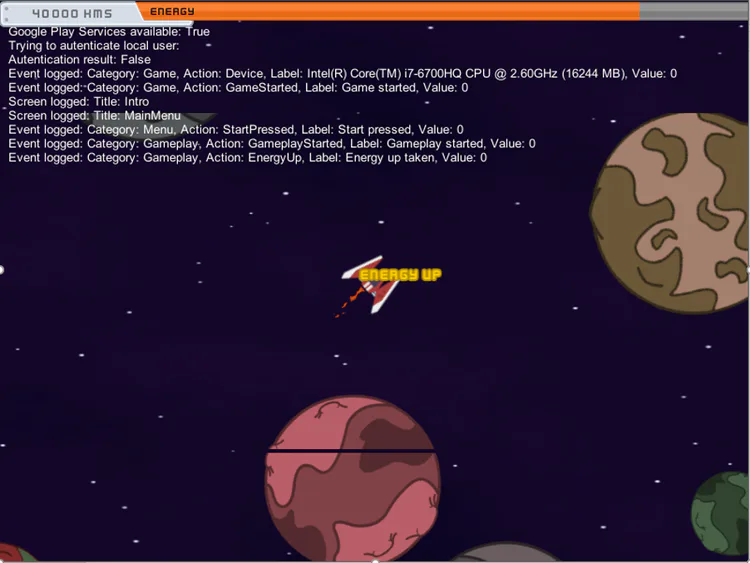

Screenshot of the main menu of the initial prototype

Unity

We start working on the game in Unity, I think back then, version 4.x was the thing, with the new UI system and everything. I had previously worked with the 3.x versions of Unity, and made some contracts games (for Flash, remember those times when Unity exported to Flash?), so we had some experience there. Even I have to debug the ActionScript generated code by Unity to determine the cause of an error in those projects.

But anyway, I’m deviating. We choose Unity because we want the game to be built in the less time possible and iterate fast. We know for sure that we could build an engine for the game, but it would take more than a year probably, just for the engine to handle everything correctly, and we want to test every aspect of game development, from concept and ideas, prototypes, implementation, testing and publishing in that year.

Another aspect was the platforms in which we wanted to deploy of the game. From the start, we wanted to create the game for mobiles and tablets, since the controls suits very well to the touch and gestures of those devices. But we didn’t have any idea how to deploy to mobile phones, other that using these tools that do it for you, and we didn’t want to program in Java. Also, we wanted the game to be free, and with IAP, since that was what everybody was doing (in retrospective, don’t know if was the best decision) and Unity provided some good options for that. So, the best option for us was Unity, and those were the times when they (Unity’s company) decided to release a free and full feature personal version of the engine, so what could stop us?

Programming

The programming of the game wasn’t a problem, since is a fairly simple game, and we had enough experience back then (I think we have more now, but who knows) to work with the problems and challenges that game was throwing at us.

The core mechanic of the game was done in like a week. I’m wondering right now how it took us 6 months to finish it… oh, I know! Working and reworking the social aspects of the game, the economy and IAP, trying different solutions, deleting code, put back code that was working before, installing plugins, uninstalling them because they didn’t do the job, hours configuring and testing Google Play, deploying to different phones, trying on that tablet that was borrowed because we didn’t have one, waiting some time to borrow the tablet again, reading a lot of documentation on how Google Play works, whew! In summary it was like 70% of the time in these stuffs. That has made me think many times what would happen if we spend 70% (and not 30%) on the development of the actual game.

Ok, to be honest, I may be lying about those percentages, because probably the UI cost like another 70% of the development time. Previously, in Unity 3.x, the UI was done with immediate mode (IMGUI) techniques, and I haven’t good experiences with that, but with Unity 4.x the way UI is done was changed, and for the better. However, we spent more hours with UI code than we would have liked.

Once thing I think we got right was the constant iteration on the game. Almost every week we have something new to show (to each other), something new to try. We implemented the controls like 4 or 5 times in like two weeks (only to end up with the variant we initially had, sorry for that Alex). If we didn’t have any new feature, we have a visual effect to add, or an update of the graphics, new item prices to try, or something else.

Screenshot of gameplay of the initial prototype

Web development

If we wanted to publish the game on Google Play (on any platform, really), we have understood that is mandatory to have a landing page, and a web page of the studio, and a domain, and a hosting, and a press kit, and YouTube videos, and gifs (think right now, we didn’t do any gif), and who knows what else.

So, besides we had done the webs fairly quickly, we spent a great deal of time configuring the hosting, the Nginx server, buying the domains, and making the videos. For the record, that was our first time doing all of that, so we learned through punches in the face every time.

Art

If you notice, at the start of this postmortem, I said we are two programmers in the studio. No graphics designer, no artist, no sound designer, no PR manager, no publisher, just two programmers. Luckily for us, my partner has some talent for art and could to handle the art of this game. Any graphics that you see in the game is thanks to him. I’m must say that I like very much how it looks.

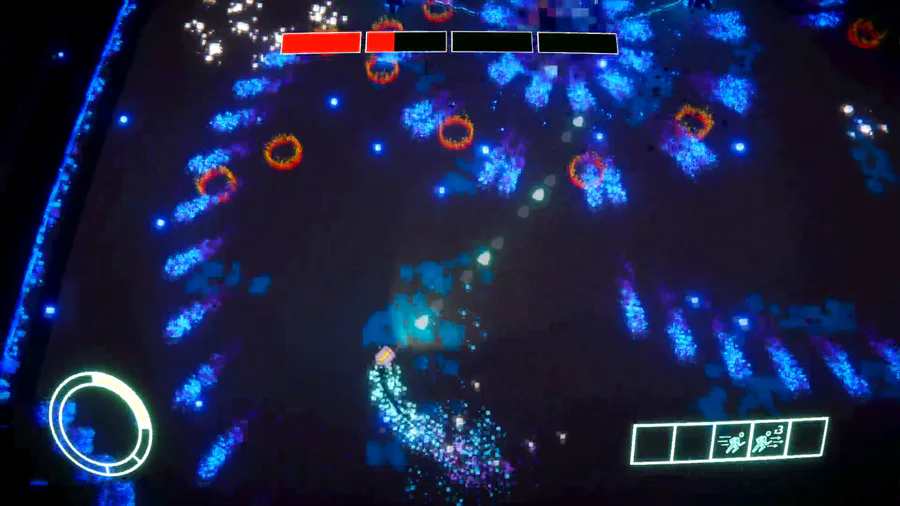

Screenshot of gameplay of the final version

IAP, Ads and analytics

This is a topic is a little frustrating for us, because we made some decisions (probably not the best ones), and some of them bring more problems than anything else.

The first decision was to use Soomla. Back then (I think Soomla is not maintained anymore), it was a library for Unity that make an abstraction over the IAP platforms, say Google Play and App Store. The library model missions, gates, virtual currencies, virtual goods, levels, worlds, and other aspects of a typical implementation of IAP. Properly configured is very easy to works with it and it do its job well. It maintains an encrypted database with all the information about what goods the player has bought, and the credits, and you can buy things with real money just for a couple lines of code. However, I had to modify some of its code in order to work like I wanted for my game, not a big deal, but I waste some time understanding the code and making the changes.

For the ads we tried AdColony, a platform that place video ads in your application. It’s fairly simple and works well, the only thing was, again, the time we need to dedicate to this and not to the core aspects of the game. We also tried AdBuddiz, another ad platform, but this time with banners. I think this one never works appropriately, at least it was very hard to get an ad in the game. We tried Giftiz as a way to bring users to the game, but that didn’t work very well either.

We integrated Google Analytics, and I must say that this was one of the smarter decision we made. When you need to make decisions, based on what’s working and what is not, you need numbers, you need metrics, and Google Analytics is very good at that. We knew, how the players use our game, how long the game sessions were, in which screen the player abandon the game, how many times the player hit the Play button, and taking into account all of these and other metrics we reach conclusions and act accordingly.

I personally think that all the work on ads was a waste of time, because in order to ads give you any revenue you need a marketing campaign, and lots and lots of downloads. And in top of that, statistic models (mean, articles on the internet) predict that only 5% of the users that download and install the game will buy something. So, you need hundreds of thousands of installations for that 5% means something. We didn’t have the money to reach a lot of people, all we have was Facebook, Twitter and a bunch of emails from friends. Surely, we launch a modest campaign that brought some downloads and installs, but it wasn’t enough to anyone buy something.

Results

With the game ready to be released, we publish it on Google Play and over the next couple of months the game had approximately 1500 downloads and installs, but the rate of uninstalls was too high, so we didn’t have more than a couple of hundreds of active devices at any point in time.

Even though the game was not a success, is a game that we published, put all of our efforts into and made the best game we could in that 6-8 months. Sure, we made a lot of mistakes, and learned a lot too. We learned what works and what don’t work in the context of our studio (remember those two programmers?).

Screenshot of the game over menu of the final version

Reworking 3 years later

Three years later Google remove my game from the store because of a privacy policy I didn’t have. So, I needed to make a privacy policy, put it online, and was the perfect excuse to open the old source code and clean up several things that I never liked.

But I don’t have Unity 4.x anymore, nowadays Unity 2018.x is the thing, so here I went and migrate the game’s source code to Unity 2018.x, remove a lot of things, clean up the code a little bit, and publish it again to Google Play.

And, I said to me, wait! Now I can publish the game to other platforms. I always wanted to make a desktop version of the game. So, I did. I spent the last weeks catching up with that old code, and made it work for desktop. I also said to me, wait! But you need a blog post, a postmortem or something, so I’m doing it.

All I want now is to have a published game that people can play, enjoy and give their opinion, if they want. Don’t know if many people will play it now, at least I know I will.

Mackno Studio team

0 comments